Every story begins in Rome. But this one is not about gladiators, nor about American tourists riding a Vespa.

Pictures by Toni Brugnoli.

Pictures by Toni Brugnoli.

Este artículo también está disponible en español.

Rome is very large. Some three million people live in la città vecchia, distributed across fifteen districts (municipi), that get numbered from the center to the outsides. The Coliseum, the Pantheon, the Fontana di Trevi and all the stuff of the movies are located in the first district. The remaining fourteen are usually left out of camera.

This story of the Air Max 97s goes against the tide: the kids of the working class neighborhoods of the periferia were the ones that started wearing the sneaker when they went bombing trains and dancing in illegal raves, to a point the shoe became an icon of young Italian (counter-)culture during the first Berlusconi years. In the nineties, if you were young and from le borgate (that’s the name the impoverished suburbs get in Roman dialect) there wasn’t much to do apart from bombing, tagging, stealing and modifying your scooter. Hip-hop? Not really. You didn’t have Internet yet.

You went down to the piazza, you met your boys and you discussed who was the one who had raised more ruckus the day before. At least in their attitude, the borgatari were closer to punk than they were to old shool hip-hop. The context helped: Rome was the only European capital in which the underground didn’t once get cleaned for ten or fifteen years. And that could only mean one thing. You had to paint.

Graffiti began in the train yards, and bombing trains still remains the purest discipline. Within the trade, risk is as valuable as style, and, in order to bomb a train, you need to accomplish a lot of risky things. First, you need to sneak in the yard, climbing, crawling or sliding through the air vent. You also need to keep everybody from hearing you (and from smelling you), and you are always in a hurry, since the guards are never too far away. Fines are steep, and the trains usually get cleaned immediately. That’s the price you have to pay if you want hundreds of people to see your name moving around town. «Se non hai mai fatto treni, sei un decoratore, sei un artista, non sei un writer» (‘If you’ve never done trains, you’re a decorator, you’re an artist, you’re not a writer’).

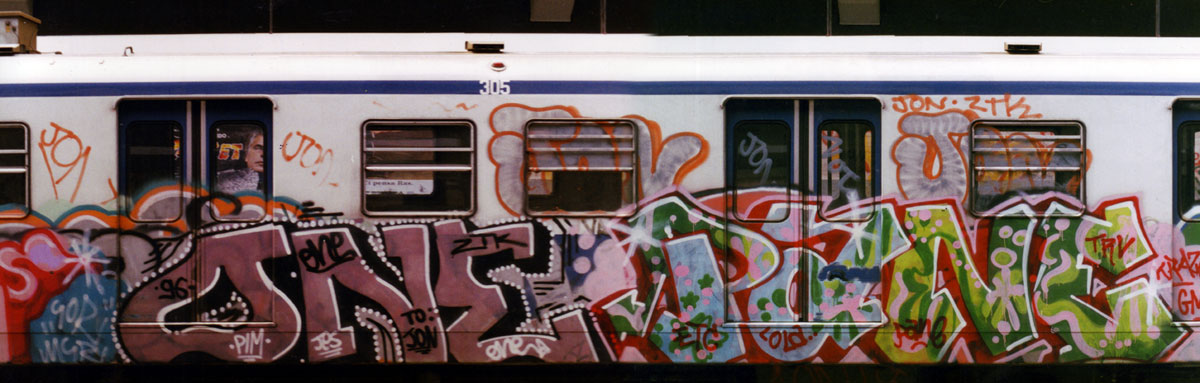

One (ZTK) and PANE (TRV), Piramide Station, Ostia, 1996 [Via]

One (ZTK) and PANE (TRV), Piramide Station, Ostia, 1996 [Via]

The graffiti scene of la città vecchia was undergoing a big change. For the first time ever in Italy, writers were doing their thing on their own, breaking free from rappers and from b-boys. The new boys in town (Rome Zoo, TRV, ZTK) were harsher: when they were not bombing and tagging, they were either in the terraces or stealing in department stores.

Stealing was a very important part of the game. Real writers didn’t pay their cans. Or their sneakers. Or their puffers. Or their scooters. They had read the stories of the Lo Lifers in The Source and they now were obsessed with technical clothing: North Face, Stone Island, ACG, Columbia, Berghaus… Getting in, grabbing it, getting out, no alarm. The idea was to show off stuff you couldn’t afford; stuff you hadn’t paid; an aspirational story.

The Air Max 97s landed in the middle of this adrenaline-driven spiral.

And what was going to happen, happened. At some point, the boys noticed the new silhouette in the window of the Foot Locker of Via del Corso and immediately understood they had to get it. La Silver represented them. Christian Tresser’s design was able to concrete their subculture of ostentation and transgression into a sneaker. The 97s looked as if they were something out of Barbarella, or out of one of Marinetti’s futurist poems. They were offensively expensive and perfect for bombing: silver stains didn’t matter, their internal lacing system made them tight to the foot and the full length air bubble softened the falls against the big, irregular stones of the train yards.

The most important thing, though? They shone. The original colorway (the golden version would not be released until 1999) matched with the silver throw ups of the new school writers, who were imposing their —more readable— block-lettered style all around Rome. And there is another important factor to our story, since trains quickly got cleaned, a necessity emerged: the photo. The piece is something ephemeral, it gets done during the night and the stakes for it not making it out of the train yard are relatively high; if you don’t get a photo out of it, you get nothing. The camera became a tool almost as important as the spray can, but not just any camera, a camera that met the functional necessities of the writer. It had to be compact, with a strong flash and a fixed, wide lens that got the colors right. First, the Kodak Cameo; then, the Olympus mju (i and ii).

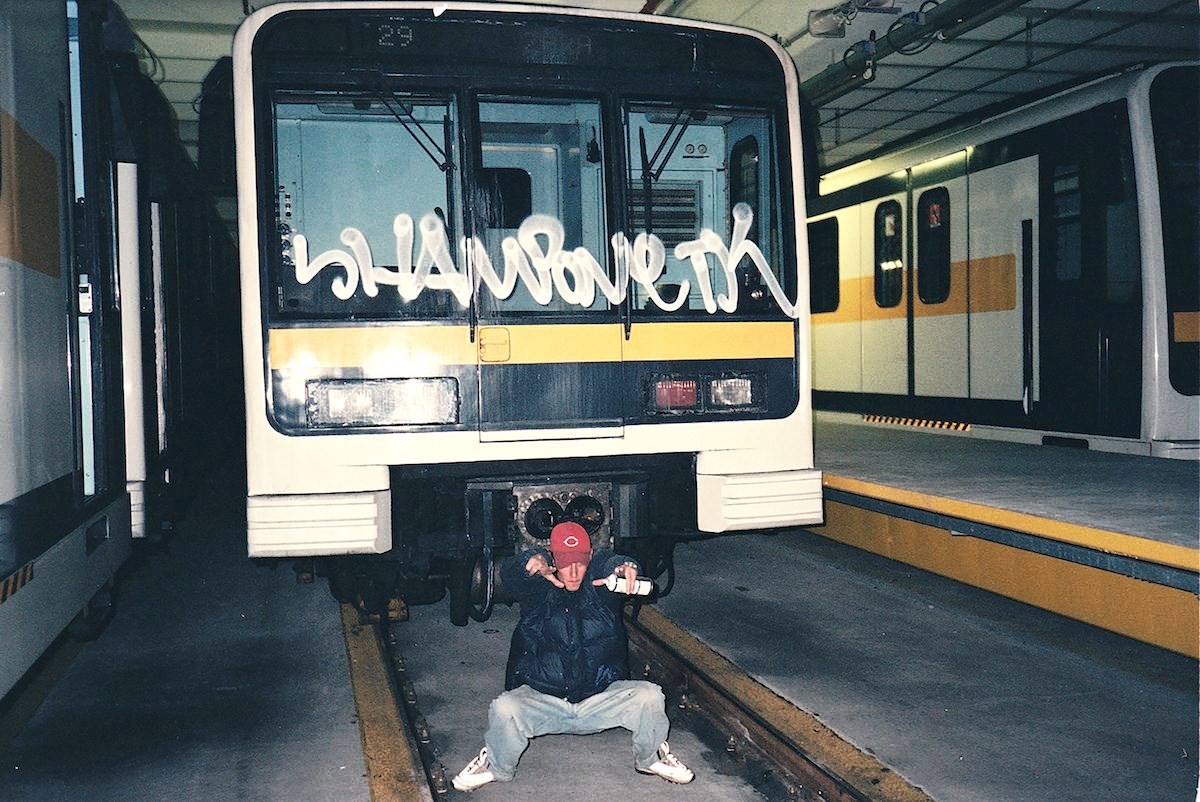

1997 was a good year for silver things: OG Air Max 97s and mju ii, Olympus’ most iconic point and shoot camera. Roman writers noticed that the 3M of the first ones and the flash of the second one got together very well, and the photo arose: squat, red eyes, covered face, the piece behind and the glare from le Silver. Writers in 2018 still take this kind of pictures (and still in 35mm, since they don’t like to leave a digital trace ?). The only problem? The sneakers also glare when you’re hiding from the guard under the train and he points at you with the torch; but the risk is an unescapable part of the game, and, for the borgatari, even an amusing one:

«When guards came after us, we screamed, ‘Dai!!! Dai!!! Come on get me!!!’ Why? Because we’d seen this going in Europe. But in Italy, nobody had seen this attitude before.»

– Chob (THE, BBS, FIA, WMD), Le Silver, p. 28.

Shampo (Lords of Vetra), Milan Metro Line 3. Picture taken from Le Silver. Property of Kaleidoscope Media. [Via]

Shampo (Lords of Vetra), Milan Metro Line 3. Picture taken from Le Silver. Property of Kaleidoscope Media. [Via]

Sometimes, the boys went up to Milan to steal 97s. There was a sports shop called Giacomelli in Corso Buenos Aires that left the stock in the middle of the store. Writers would get in wearing old shoes, try le Silver on, leave the old pair back in the box and make a run for them. Voilà, new Air Maxs. That easy.

Milanese piazza boys started jumping in, too. Mind, Dumbo, Spice… the writers of VDS and Lords of Vetra understood the codes and became the first ones in assuming the Air Max 97s as a status symbol, a status symbol that matched their tricked-up Honda ZX Dios. All city follows. And by all city I mean all city. Even fashion designers. Even Inter players.

Lombardy’s capital is a very strange place. Look at what happened to Marcelo Burlon: he arrived from Argentina when he was 21, he became the king of the club kids of the city and then he moved from the most exclusive party of Milan’s Friday night to the catwalk of Florence’s Pitti Uomo. The creator of County of Milan says his brand ought to be understood as a «multicultural whisk of fashion, music, clubbing and radical beauty»; and, to be honest, the city itself could be understood in the same terms.

Milan constitutes a unique space for the simultaneous impulses of Italy’s different suburban cultures to meet. Maybe like nowhere else in the world, the streets stablish a direct dialogue with fashion powerhouses, which, in turn, give back an immediate impact to the streets. In 1997, the topic of the conversation was clear: everybody met around le Silver. Gabbers were in need of a shoe that —unlike Buffalos— allowed them to dance to a music that presented more BPMs year by year, and gravitated towards the Air Maxs because of their retro futurism. Young fashion designers found a reaction against minimalism in them, in the same line of what (first) Helmut Lang and (then) Margiela and the rest of the Belgians were doing at the time. Next thing you know? Giorgio Armani waves after his Milan Fashion Week ‘98 show wearing a turtleneck, wide- legged trousers and some OG Air Max 97s. Six months later, Dolce&Gabbana use them again in the runway and the rest is history: Cannavaro, Materazzi, and then every Italian under thirty, almost without exception. In 1999, if you didn’t have le Silver, you couldn’t be cool even in the smallest village of Salento.

The fever lasted well into the 2000s, and it has never really gotten away. Lately we have seen a revival motivated by limited releases and anniversary editions that invade our feeds. But that’s not the important thing.

The important thing is that a story so big all started in the peripheries.

All this pictures are Toni Brugnoli’s. Toni Brugnoli (1990) is a film photographer from Milan whose work constitutes a visual reflection on the culture referred to in this article. Few people explore the peripheries as well as Toni does.